love island has a race problem

Last year, I wrote my dissertation on the portrayal of black women in British reality television. In this chapter, I explore the treatment of Season Five Love Island contestant Yewande Biala.

A Brief History of Love Island and its Politics

ITV’s Love Island (LI) has had a relatively long history on the silver screen, originally starting as a celebrity dating show in 2005 before being cancelled in 2007, and then rebooted in 2015- this time with attractive, but ‘ordinary’ people. The celebrity status of the contestants may have been abandoned, but a large part of the show still revolves around desirability, with an emphasis on being conventionally attractive.

Every summer and winter, five women and five men are sent to an island to find love, ‘coupling-up’ with their co-contestants while viewers at home vote on who to ‘dump’ from the island. LI uses the physical appearance of its contestants to market the show, sharing swimwear photos to build anticipation weeks before the premiere of a new season. The series has always been steeped in scandal, receiving consistent complaints since its first season and retaining a consistent position in the top ten of the most complained about UK television series (Ofcom, 2023).

Despite its negative reputation, LI has managed to remain largely apolitical, assumingly cutting out the political or social commentary between contestants in production. Due to this, Love Island is a perfect example of post-racial reality television- despite the series sparking discourse about the portrayal and treatment of black women in UK media, it still manages to completely omit any mentions of race throughout the series. Altogether, LI presents a Eurocentric, heterosexual and exclusive hegemonic micro-society (Ramsden, 2018).

Although producers have never explicitly stated that conversations about politics are banned on the show, in an interview with the BBC, previous contestant Chris Williamson stated that islanders are not permitted to speak about the “outside world” while in the villa (Williamson, 2019). Additionally, Sherith from Season Five of Love Island was given a caution from the show producers for using the word “lighty” to describe biracial Amber Gill, and for saying “rape” in a “serious conversation” (Culliford, 2019, Sohifano, 2019). From this, we can speculate that conversations revolving around issues that are deemed as too heavy for the show are at least censored, if not prohibited. The focus on beauty, heterosexuality and traditional portrayals of both femininity and masculinity create a conservative undertone to the show, as journalists Chakelian (2017) and Foley (2018) have discussed.

Black Women and Love in the United Kingdom

The representation of black women in British-based reality television dating shows is important to study, as it is the main platform where black women are presented as viable love interests in British television. It’s rare for black women to depict love interests in fictional films and television, and when they do they are often treated as disposable- Magical Negresses there to help their significant other work through dilemmas until they are no longer needed, placeholders until the real love interest, usually a white woman, is written into the story (Adegoke, 2019, Haile, 2023).

In their research on the experience Black Americans have while using dating apps, Celeste Vaughan Curington, Jennifer Hickes Lundquist and Lin (2021) discover that on average, across the five major dating apps, white app users rate black users below average, at two out of five. In their interviews, they learned that young black men and women feel both hyper-visible and invisible on dating apps, experiencing either fetishisation for their race or invisibility as others ignore them (Celeste Vaughan Curington, Jennifer Hickes Lundquist and Lin, 120-121, 2021). This study focuses on the experiences of Black Americans, but it can be linked to what Black British people in the United Kingdom deal with today.

In interviews with Olivia Petter for The Independent, Black-British single women shared stories of being called an “experiment”, being approached because “black girls have better asses” and overall finding less success on online dating apps (Petter, 2018). The issue prevails for all black women across the diaspora, but research reveals dark-skin black women experience more rejection due to their perceived manliness, whilst light-skin women are deemed as more attractive, albeit, fetishised (Okazawa-Rey, Robinson and Ward, 1987, Wade and Bielitz, 2005).

Since the early days of Love Island, the show has received criticism for lacking diversity. Its initial three seasons completely excluded representation of black women, implying that they weren’t included in the target demographic. This reached a boiling point in 2017 when out of the thirty-nine female contestants that appeared on season three, three were mixed race and none were black. In a conversation with Yomi Adegoke (2017) for ELLE UK Rachel Christie, one of the biracial girls, expressed that:

'When it comes round to the guys picking the women, you know they're not going to pick you. A lot of people are brainwashed into thinking [black] is not beautiful. And obviously that's a load of rubbish.'(Christie, 2017)

Although Love Island producers would refrain from casting such a monoracial cast again, Christie's experience referenced in the above quote would be echoed by multiple biracial and black women who went on Love Island in the following years. The first black woman in the series was Samira Mighty. Her experience and portrayal in the villa sparked debates about stereotypes in the show. Initially, Samira was marketed as the “sassy” islander, a common stereotype for black women in film and television. During her introduction interview, Samira’s promotional video lacks anything related to romance or love, despite the premise of the series. This is in contrast to the rest of the main cast women, who all talk about previous romantic experiences and what their type is. Before she even enters the villa, Samira is typecast as the sassy black best friend stereotype, which Liberto (2023) connects to the historical depictions of Black women as Sapphires and Mammies in Western media.

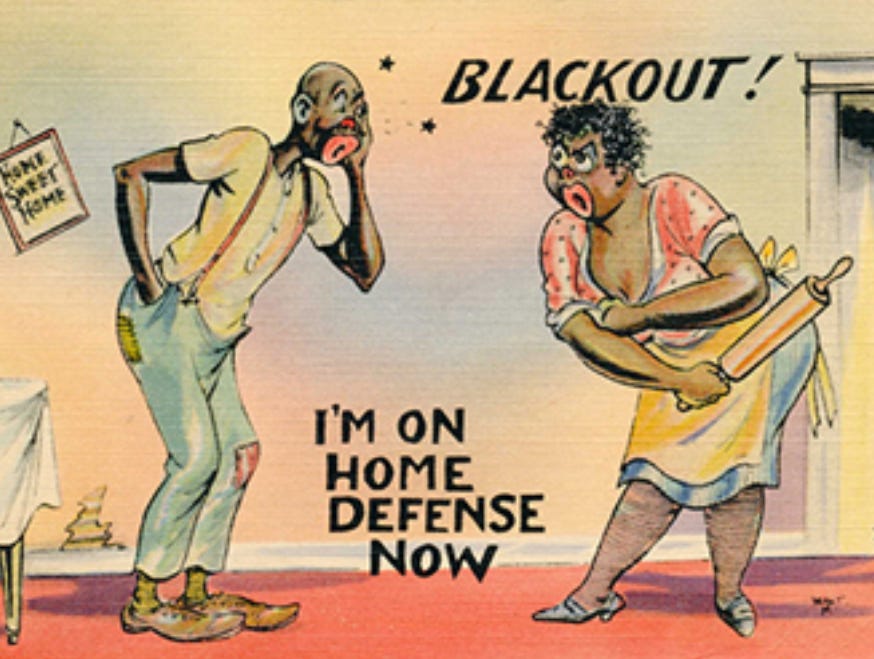

The Sapphire caricature is verbally aggressive and nagging, while the Mammy is a self-sacrificing caretaker whose priority is the white family that employs her (Reynolds-Dobbs, Thomas and Harrison, 136, 2008, Jerald et al., 488 2017). Applewhite (2019) argues that the “sassy black friend” is a modernised hybrid Mammy/Sapphire caricature, using the supposed ‘aggression’ and boldness of black women as comedic relief. Despite her ‘feistiness’, she’s a reliable source of advice and comfort for her white friend(s). Examples of this trope in fictional television include Mercedes from Glee (2009) and Ivy from Good Luck Charlie (2010), two characters whose aggression and forwardness are played for laughs.

From the first episode until her exit, only one of the male contestants of the show showed any interest in Samira. Samira told Black Ballad her experience was “a cycle of: ‘what’s your type? Blonde and blue eyes? And I used to be like, well I’m neither!” (Mighty, 2023). Despite this, Mighty felt her time on the show wasn’t wasted as she was able to show the black women watching at home that a woman like her could be on a show like that, comparing it to The Only Way is Essex and Made in Chelsea which are two other shows with predominantly white casts. However, Samira’s experience calls into question the positive impact of diverse casting, leaving black women across online media wondering if appearances on shows like Love Island do more damage or good for their representation (Katsha, 2019, Mamora, 2021).

Within this context, black women and their experience on British dating reality television becomes complicated. The main focus of this chapter is the experiences of Yewande Biala and Amber Gil in the subsequent season of Love Island, their representation, and their reflection on race and desirability in reality television.

Yewande Biala - Colourism, Desirability and Visibility

In Season 5 of Love Island, Yewande Biala, a Nigerian-Irish scientist, entered the villa as an original cast member. She was joined by Amber Gil, a Trinidadian-British biracial woman, who would go on to be the first black woman to win the show, whilst Yewande was the first female original cast member to leave the villa. The polarising experience and representation of Yewande and Amber provide an interesting example of the experiences of dark-skin and light-skin black women, specifically how their pursuit of finding love is represented.

From the first episode of Season Five, Yewande faces difficulties in her pursuit of love. As part of Love Island tradition, the initial five women stand in a line and are presented with each male contestant, one at a time. In a real-life dating app scenario, the women then step forward for any guy they find attractive. The men are then prompted to pick a girl to couple up with, having the final say- whether they step forward or not.

Yewande is one of the few female contestants which no male contestant choose. Without a script, Yewande is immediately painted as less attractive than her white co-contestants, confirming the dominant stereotype that dark-skin black women are undesirable. Multiple focus group studies on college-aged African-American women have proven how widely this stereotype has influenced perceptions of self-worth and desirability, with both Snider and Rosenberg (2006) and Bond and Cash (1992) coming to similar conclusions after their respective research.

Yewande chooses to step forward for Joe, a British man, describing him as “cool” and saying she believed they’d get along. Legal scholar Ralph Richard Banks pontificates that the hesitance from Black women to reciprocate or initiate expressions of attraction to White men is linked to the dominant belief that only black men are attracted to black women. This experience differs for biracial women, who are more open to interracial dating. The coupling-up scene in Love Island reflects both these studies’ findings, as Yewande steps forward for White-British Joe who picks White-British Lucie over her, and Amber steps forward for White-British Callum who decides to couple up with her. This scene sets the tone for the rest of the season as Love Island continues to conform to dominant beliefs about black women and love rather than challenge them, much like it continuously upholds heteronormativity and patriarchy.

For the first few episodes of the season, Yewande receives little to no air time, which was observed by viewers at the time. In a statement to The Independent, a Love Island representative stated: “As we have said before, it is not possible to show everything that happens in the villa due to time constraints”. Despite this, viewers of the show including ex-Love Island contestant Marcel Sommerville highlighted the decision to cut specifically Yewande’s air time and focus on the romance arcs between several of the white islanders (Young, 2019).

In their pursuit of diversity, ITV made sure to cast multiple people of colour in Season Five of Love Island. Five of the ten original cast members are people of colour the highest ratio since the show’s beginning. However, representation in reality television doesn’t stop with casting. On a television show where viewers vote for their favourite couples and islanders to stay, visibility is an important part of the process. Goepfert (2016) highlights this in an analysis of the invisibility/visibility of black womanhood on television, reflecting on the hypervisibility of negative stereotypes of black women such as the Sapphire and Jezebel, and the invisibility black women on reality television face when they don’t ‘act out’ according to these stereotypes. Although the producers of Love Island are hesitant to suggest any element of the television show strays from reality, multiple islanders have shared that interactions they had were completely edited out, removing important context. With this in mind, it is important to critically analyse what is kept throughout the season, and how this adds to the invisibility/hypervisibility experienced by Yewande.

Despite being in the main cast, Yewande’s airtime is limited until her coupling with Danny is challenged by the entrance of Arabella, a blue-eyed, blond-haired model. Prior to her entrance into the villa, Danny tells Yewande that his “head can’t be turned”- that she is the only girl he has eyes on. But after Arabella arrives on the show, Danny tells her privately that there’s an “instant connection” between them. At this point, Yewande’s representation takes the form that many reality television shows including black women do- she is portrayed as desperate and un-loveable.

In her thesis about the stereotypes around black women in The Bachelor and Ready to Love, Monica Wilson (2022) observes the common trend of black women on reality dating shows confessing to dealing with unacceptable behaviour from romantic partners out of fear of loneliness. Although this reflects the experience of many black women in the Western world, the constant reminder through media creates a cyclical effect.

Earlier in the season, Yewande expresses experiencing rejection and always feeling “second best” in romantic endeavours, and as Danny starts showing a clear interest in Arabella; she cries to her fellow female islanders about never being “good enough”. This sentiment echoes the Disposable Black Girlfriend trope earlier discussed. Yewande’s upset turns to anger as she comes to terms with the unfairness of her situation, and is confronted by Arabella. Their interaction goes as follows:

ARABELLA: I just wanted obviously like see how you are with the whole Danny thing, I just wanted to have a little catch-up?

YEWANDE: Um yeah I think at the moment like we're just really strong, and going forward I think everything's looking goodI I'm excited about the future and I think it's gone well

ARABELLA: Because obviously today he did say that both of us can’t deny that there is a connection

YEWANDE: Between you and him?

ARABELLA: Yeah

YEWANDE: Okay

ARABELLA: So obviously from my point of view I’m a bit like, he’s telling you one thing and me one thing. He still feels like he still wants to get to know me right you know like earlier on when I was chatting on the bean bag with him and Anton and then you came over and you literally just like sat on him which, yeah I have no problem with like, you coming over having a chat but I just feel like it's a little bit like territorial?

YEWANDE: Not really I think really the only reason I did that was because he said another issue that we had was that I wasn’t showing enough affection

This conversation is filmed to clearly show the reactions of both women who sit across from each other. Absent of dramatic zooms and sound effects, the tension builds through a constant cutting between the two contestants, never putting them in frame together. Both women remain composed during this conversation, and although tension is felt due to both the subject of the conversation, and the editing, the interpretation by the popular media of this interaction as an “argument” is subjective.

Arabella calling Yewande “territorial” for sitting on Danny’s lap is a layered statement. On a show revolving around love, where physical affection is treated as a reassuring show of commitment, behaviour like this is normalised. But by framing Yewande as “territorial”, her depiction as the Desperate Black Girl is exemplified, even though the affection was requited and requested by Danny. Additionally, the Sapphire caricature is commonly depicted as being “territorial” and overly defensive of her partner. The articles written about the situation repeatedly labelled Yewande as “desperate” and “furious”, only further mediating this stereotype of Black women looking for love.

An extremely similar situation happened with white-British Moll-Mae and Tommy Fury, as bombshell Maura Higgins entered the villa earlier in the season. Instead of “desperate” and “awkward”, Molly-Mae was empathised with by a majority of mainstream media, while Maura was chastised for coming between a couple- even though Tommy was returning the advances. The juxtaposition of the media circus around these two incidents reflects the effect of stereotypes in readings and interpretations of similar behaviour exhibited by people of different races. It is worth observing however that in both circumstances the majority of the coverage was focused on the women involved, absolving the men.

After this interaction Yewande expresses frustration to her fellow female contestants, explaining what Arabella said to her. This situation plays out over two episodes, considerably more air time than Yewande received throughout this season. In the end, Danny chooses Arabella over her, and Yewande is unceremoniously ‘dumped’ from the island, concluding her ‘arc’.

Although Yewande was a fan-favourite (McLauren, 2021), the majority of her air time was restricted to moments when she was either provoked to anger or upset, despite being in a couple that was according to her and Danny, getting better every day. Love Island doesn’t allow Yewande to be shown being loved and in love, leaving the popular media discourse around her time on the show to mostly revolve around her high emotions and depicting her as the Angry Black Woman (ABW). Talking about her and the other women of colour’s experience in the villa in an interview with BBC Radio 1xtra, she states:

“We didn’t find anyone who liked us. It was always someone coming in and saying ‘my type is blonde and petite’. We’d just look at each other and say ‘they’re obviously not here for us’.”

The post-racial, apolitical climate of 2019’s season of Love Island means race was not discussed inside the villa, but once outside, Yewande was able to shed light on the secret feelings of the women of colour from the main cast of Season Five. This quote captures the issues black women face on dating reality television. No matter how much they adhere to Western beauty standards through a slim build and straightened hair, their experience will always differ from their White co-contestants due to hegemonic European beauty standards.

The other black woman on the show, Amber Gill starts her Love Island journey slightly better. As a biracial woman, Gil benefits from colourism’s preference for light skin, being picked by one of the male contestants in the first episode. Although light-skin women don’t typically experience as much masculinisation and dismissal in the dating world, they do experience over-sexualisation and fetishisation. Throughout the first few episodes of the series, various male contestants describe Amber as “stubborn”, “feisty”, “and rude” but also as “smoking hot” and “fit”. Amber describes herself as “self-assured” and confident, not accepting attention from the male contestants who come to her after failed attempts with the other women on the show. At the time of airing, popular discourse around early season 5 Amber was that she was “rude” and “stuck-up”.

Despite Amber consistently receiving air time when she’s rejecting a love interest’s advances or arguing with the men at the villa, popular discourse around her softened as viewers were exposed to her ‘kinder’ side and her platonic relationships with the women on the show. This twist captures the power production has over who the public sympathises with, as editing out the moments she shared with friends may have confirmed the dominant negative reception reported by popular media. Cossey and Martin (2021) argue that Amber’s representation as a protective friend, “empowers not just her own voice, but the voice of a friend who has been silenced” (Cossey and Martin, 1210, 2021). Instead of being villainised and stereotyped like Yewande, Amber’s expression of anger is represented as a form of justice (Alao, 2019).

Amber then goes on to experience her own Disposable Black Girl story arc as the man she’s coupled up with leaves her for another, whiter woman. Through all this, the public consistently votes for Amber to remain in the villa, leading to her winning the season with partner Greg O’Shea, and becoming the first black woman to make it to a final and win Love Island. Amber’s win and ‘story arc’ exemplifies how narratives can change perspectives on ethnic minorities. Although her time in the villa was not without its issues, she was able to be represented outside of the confines of black female caricatures, aided by the choice from producers to consistently place men in the villa who were interested in her.

The polarising experiences of Amber and Yewande are case studies for the positive and negative outcomes of the representation of black women in British reality dating television. Yewande’s experience proves that simply placing black women in television shows without rethinking the structural issues in casting and production affects their experience on screen. The lack of this level of care enabled a simplistic ABW caricature out of Yewande, denying her nuance or complex emotions. It would be ill-minded to deny the hand colourism played in ensuring Amber Gil had a more successful experience on the island.

need to read the entire dissertation lowkey

This was fascinating - great read!!